Tests as Tools for Understanding

It was only recently that I realized just how much tests are an integral part of how I code. I use them constantly, allowing them to influence every stage of my workflow, so I thought I’d share some ways in which they help me.

I’ll break the ways tests are part of my workflow into four camps: tests are tools for understanding, counselors of design, drivers of implementation, and pillars of refactoring.

Tools for Understanding

When working on a feature, I often find pieces of code that I have not seen before. In order to better understand the class or method, I like to use tests as documentation and as a way to explore the code’s functionality.

Documentation

The RSpec documentation format is very helpful for this. You can simply pass the fd flag (short for --format documentation) when running specs.

As an example, let’s look at some tests for the factory girl gem. Having cloned the repo, we run the following spec,

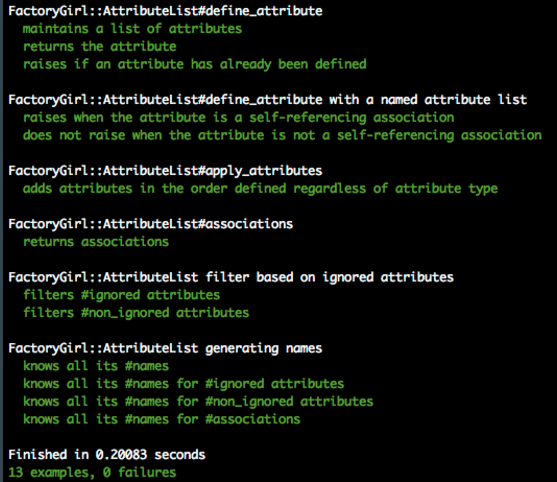

rspec spec/factory_girl/attribute_list_spec.rb -fdAnd we get the following,

At a glance, we get a good idea of what the class does, even though we’ve never seen the implementation of the code:

- There are at least three instance methods:

define_attribute,apply_attributes, andassociations. - The

AttributeListclass seems to filter the attributes and generates names for attributes.

In addition, looking at the descriptions of each test example we can gain more information.

For example, the method define_attribute seems to,

- define an attribute,

- maintain a list of all attributes that have been defined thus far,

- return the attribute defined as a return value, and

- validate that an attribute has not been defined and that it is not self-referential.

Of course, this is only true so long as the description of the tests matches what the tests are actually asserting, an assumption that may or may not be trivial depending on the code base in which you’re working.

As a side note, I think it is very helpful when a class uses the describe '#instance_method' syntax (as the example above does) and the '.class_method' syntax.

That allows us to determine what is the public interface of the class and presumably what are its return values.

Exploration

When I find a piece of code that I need to understand with incomplete tests or no tests at all, or when I want to interact with a new library, I use tests as an exploratory tool.

Often, I will start with no knowledge of what a method does. So I’ll start with an almost ridiculous test. For example, I may write something like this,

describe BlogPost, '#publish' do

it 'works' do

post = BlogPost.new

response = post.publish

expect(response).to eq 'hello'

end

endThat test will fail, unless of course the method publish on a new instance of a blog post actually returns 'hello', which is unlikely in this case.

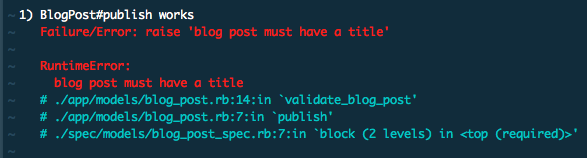

The test failure is important because it gives us information as to what the method actually needs or does. Say it returns the following,

Clearly, the blog post needs a title.

This points to a very important lesson about tests: listen to the error messages. They are there to help. And sure, we could have learned that we needed a title by looking at the implementation of the method itself, which in fact would have likely been open in a different pane next to my tests. But if that error came from a very confusing method, or if it was an unexpected error because it came from some class in the inheritance chain, this would be the fastest way to find out.

What I typically do now is to make the original test pass by updating the expectation and the description, so as to have documentation for the future. Then I write a second test, correcting the previous mistake, in order to see what else we can learn via testing.

So we might update our tests to look like this,

describe BlogPost, '#publish' do

it 'raises when post does not have a title' do

post = BlogPost.new

expect { post.publish }.to raise_error 'blog post must have a title'

end

it 'works' do

post = BlogPost.new(title: 'test first part-1')

response = post.publish

expect(response).to eq 'hello'

end

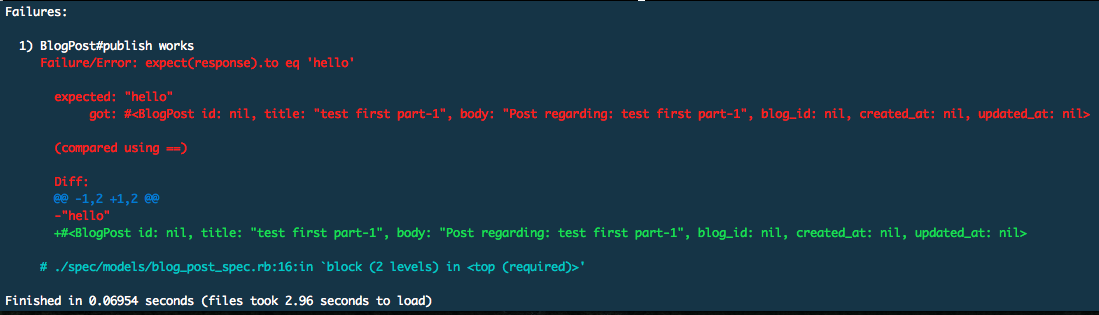

endNow we see that we ran two examples, only one failed (as expected), and the failure messages is

It seems that if we provide a title, invoking publish works, and it returns a blog object.

We can also see that a blog post can be published without a body, and a default body, based on the title, will be automatically set.

Though this might seem like strange behavior, for the sake of this blog post, we will assume that the behavior is desired, and thus the response is a valid one.

Nevertheless, I would like to document that behavior since it is not intuitive, and I now have knowledge of it.

So, I would update the tests to look like this,

describe BlogPost, '#publish' do

it 'raises when post does not have a title' do

post = BlogPost.new

expect { post.publish }.to raise_error 'blog post must have a title'

end

it 'returns the blog post object' do

post = BlogPost.new(title: 'test first part-1')

response = post.publish

expect(response).to eq post

end

it 'sets the default post body based on the title if body is missing' do

post = BlogPost.new(title: 'test first part-1')

published_post = post.publish

expect(published_post.body).to eq 'Post regarding: test first part-1'

end

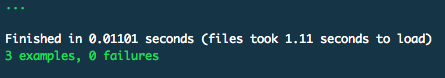

endAnd running them again I get

Since this seems to be everthing that the publish method does, I might conclude my exploration here.

In our example, it only took three tests, but it could take any number of tests, and I usually repeat the process

described until I get all of my tests to be green.

A last note on exploration:

I think the method of documenting code as we explore its workings is extremely valuable, not only for the person doing the exploration but also for those who come after. If this is a method that is difficult to understand, then we know it takes time and brain power every single time a developer needs to understand it. In other words, it is costly. But we can reduce that cost with good documentation. Having tests explain the public interface and its return values is an excellent way of doing that. In fact, having created those tests will allow someone to confidently refactor the complex method, making it easier to understand.

In the next posts on this series, I will look at how tests help with design, implementation, and refactoring.